Public libraries located in rural locations have unique capabilities to generate social wellbeing outcomes in their communities. Through conversations with over 200 people in eight remote towns across the US, we heard rural residents describe the “good life” in their own terms, and the ways in which their local libraries enriched that life.

Key Findings

- Rural residents prioritize social connection and nature over access to amenities.

- Rural libraries connect residents in a variety of ways, over time, impacting core vitality and security in their unique communities.

- Rural library directors are bonded to the community, described as selfless and engaged, and are seen as both belonging themselves and active in creating belonging in others.

Community Conditions

Rural communities are not static. Interviews revealed an ebb and flow of community wellbeing over time, and an enduring sense of heritage and shared identity. Connection to place is strong in these communities; it’s the glue that holds together a diverse group of people with all their idiosyncrasies. Understanding community conditions provides clarity and context to understand the library’s impact on wellbeing and how individuals experience personal wellbeing.

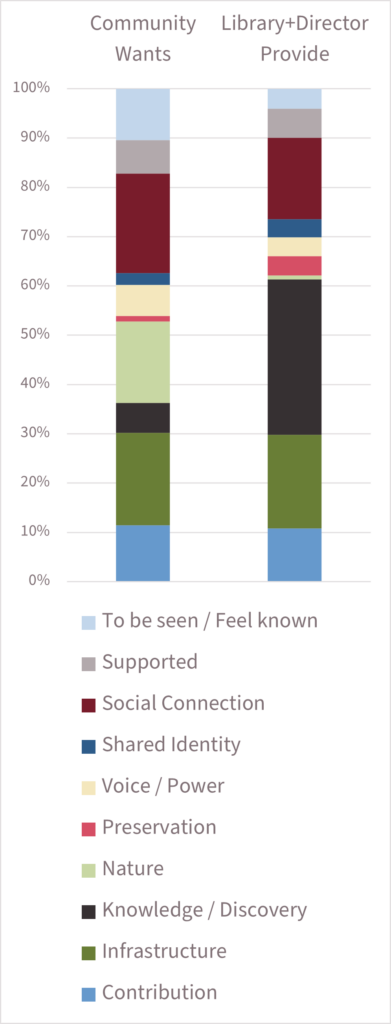

What Communities Want & What Libraries Provide

Interviews began by asking the subject to describe their ideal community. The answers revealed a range of values, wants, and needs, but also some striking similarities across geographies. Over 98% of our interview subjects said that where they currently lived represented their ideal community.

Feelings of being rich, happy, healthy, and safe were found to be much higher than publicly available quantitative wellbeing data would suggest.

And in these locations, the library played a strong role in facilitating connections among individual residents— and between residents and their local culture—which created feelings of security, richness, and health.

People we interviewed often mixed their view of an ideal community with their perception of the way their town was in the past. This was found to be more than nostalgia.

We found a deep desire for community self-determination and the deep social bonds that create strong networks of mutualism throughout the community.

Mutualism was a major feature in communities where the phrases “support,” “social connection,” and “to be seen/feel known” were frequently stated in interviews.

Elements of the Good Life:

Social wellbeing as described and distilled from the interviews

Contribution: To give to others through skill / knowledge share, volunteerism, philanthropy for the benefit of the larger whole.

Infrastructure: Built structures including telecommunications, facilities, and the equipment required to use it.

Knowledge / discovery: Generation of skills, new ideas, concepts, and ways of being.

Nature: Land, bodies of water, animals, and plant life which are both managed and unmanaged.

Preservation: The capture, collection, and maintenance of culture, heritage, artifacts, language, stories, and histories of the multiplicity of cultures which exist in a place.

Shared Identity: A commonly held belief about the community, its geography, place in history, place in socio-political landscape, and/or cultural heritage.

Social Connection: Social belonging, attachment to others outside of work and family.

Supported: Experience when others act to benefit the individual, family and/or organization.

To be seen / feel known: To live without anonymity within the community.

Voice / power: Ability to enact independent choices about one’s own future and the future of their community.

Pathways

People who share a common geography, with a shared sense of history, develop not just physical pathways to get them from one place to another, but experiential pathways as well.

We call the processes by which libraries positively impact social wellbeing Pathways to Wellbeing, and offer them as descriptions of what libraries do when they design, build, maintain, reinforce, and sometimes divert common life paths toward positive wellbeing outcomes in their communities.

Where we observed libraries that actively connect individuals to their community through a long term, multi-step process that is custom-made to both the individual and the community, they were impactful. We found few to no shortcuts. The process takes time, a personal touch, a deep understanding of what makes a place unique, a building of trust, the ability to see the full variety of community assets and know how to activate them, and a lot of passion for the inherent beauty of a particular place.

Libraries wanting to improve their social wellbeing impacts may need to revise their self-perception to be not just a recipient of mutual support, but an active facilitator of it. If asked to describe in one term what Pathways to Wellbeing boils down to, we would say, emphatically, social connection. And if there is one thing to take away from this research, it is that increasing widespread and deep social connection, any way you can do it, will lead to improved wellbeing. We heard this described in terms of belonging, mutualism, and self-determination.

Pathways of and to Belonging

The library building as a place matters, especially where few other options for meeting exist. At the library rural residents experience neighborly chats, personalized service, and satisfaction of the deep human need to be seen and feel known by others. It is the entry point to belonging for many newcomers, and the nexus of connection which reinforces belonging over time.

Pathways of and to Mutualism

Mutual support makes rural life feel secure and rich. Where we heard residents discuss their feelings of belonging in the community as well as in the library itself, those feelings were commonly associated with their personal stories of reciprocity. They contribute to the community and library, and in turn the library and their neighbors support them. Libraries maximize collective contribution.

Just as small contributions of money can give access to a large selection of library books, small contributions of time and talents can give access to large amounts of support.

Commonly library directors do extraordinary things for individuals in the community, but in the context of high mutualism this is the norm, not the exception.

Pathways of & to Self-determination

Small town politics, similar to big town political systems that give some individuals more access to power than others, operated in all of the communities we studied to varying degrees. But where we heard residents use language of personal agency and collective power, we saw the library directors using their own social capital to facilitate individual voice in decision-making processes, and collective power in community-wide initiatives.

Throughout all of these points of intersection between social wellbeing and public library service in remote rural communities is the notion of community identity and narrative control. Stories are powerful, and who in a community is empowered to develop and tell the story matters. This is one of the important ways in which residents express their belonging and build a sense of control over the future, and to varying degrees our case study libraries played a role in providing access to those narratives.

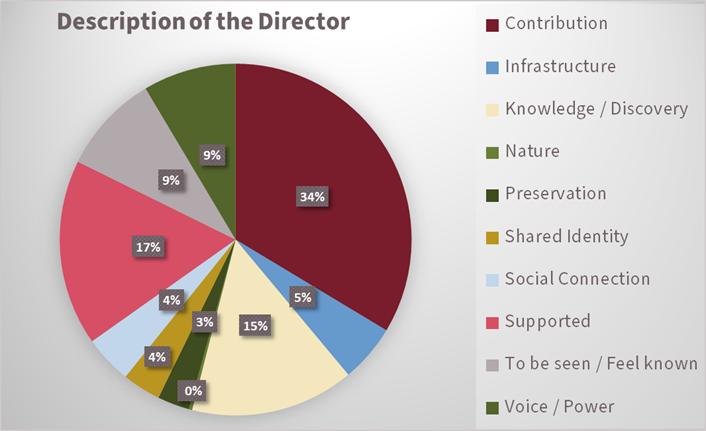

What We Learned about Library Directors

Our case study librarians do not follow a playbook. Their work is derived from a deep connection to the community, and a sincere desire to help make their town the ideal place to live. They are able to develop feelings of belonging and acceptance in others, because they themselves feel like they belong and are accepted.

The attributes of impactful library directors exist independently of the external support resources available to them. Rural public library directors are important to the operational effectiveness of the library and demonstrate a wide variety of approaches intuited and tailored to the unique needs of the community. They are described in terms like: engaged, active, giving, outgoing, creative, approachable, and personable. They support education for all ages, are good with kids, are community-oriented, do a lot of outreach, are great at picking out specific books for specific people, and have a knack for drawing out talents of community members.

Directors Build Pathways

Directors in these communities had a style of service residents called “old timey.” What sounds like a quaint small-town-ism is critical to how library staff reinforce, re-route, and build pathways to wellbeing. “Old-timey” is personalized and purpose built for both the person and their situation. In aggregate, the director builds service that recognizes the many ways of being and doing that community residents need and aspire to, within the context of that specific community.

Through this continual return to the humanity of each community member and the director’s authentic love of place, the foundational elements required for community wellbeing are formed.

For the Full Report

“Pathways to Wellbeing: Public Library Service in Rural Communities” is available: https://osf.io/m9kwu