Rural communities1 with public libraries have higher graduation rates and longer lives, among many other benefits. Field research conducted by Rural Libraries & Social Wellbeing demonstrated that rural communities use their library as a social, cultural, and educational anchor, allowing for multi-dimensional social wellbeing impacts that have broad and deep impact.

While there is recent research interest into how public libraries facilitate positive outcomes across populations served, we found that rural libraries create positive outcomes across sectors, something that has not yet been closely examined. By focusing direct research on rural communities to understand with more nuance their unique strengths and challenges we illuminate the role of effective libraries when they positively support wellbeing.

SOCIAL WELLBEING

Social Wellbeing is a term used to describe the multiple dimensions impacting quality of life for an individual, community, or region. Based in the capabilities approach and used in impact studies of museums and libraries—most notably in “Strengthening Networks, Sparking Change” (Norton & Dowdall, 2017)—social wellbeing in practice is similar to social determinants of health or social indicators measurements. Using it as a measure implies that the researcher recognizes the tightly bound interrelationships between economic, emotional, social, educational, environmental, security, voice/power, and health systems that impact on how a person experiences their life in a community.

HOLDING SPACE: Community Anchor & Catalyst

Public libraries in the US serve all different scales and types of “publics.” An urban library like Queens Public might have dozens of branches where visitors can engage with services and attend family program, roving bookmobiles, correctional facilities services, dedicated research facilities, and a large outreach staff. Rural libraries serve similarly diverse needs in buildings which are on average 3,150 square feet (PLS 2019), with nearly 1 in 6 coming in at 1,000 square feet or less. Though physically small these spaces create a powerful place to anchor community activity and facilitate resident mutual support by connecting them to each other. Connections are made through formal programming, like book clubs and classes, and also by simply holding space for interaction in an unrushed zone, or what Eric Klinenberg dubs “social infrastructure” (2019). What matters for many rural residents is that the library is there and it is an institution that belongs to them. As one rural resident put it, “This is convenient. It’s close, easy. It’s ours. That’s the point. It’s ours.” (Iowa, transcript #2-2-01)

Rural communities throughout the US have experienced consolidation for the past forty years. The mark of that lack of community control is palpable in resident interviews: where residents said they were not living in their ideal community, it was nearly always because of lack of collective self-determination over a major issue (eg., political structure in a town in Mississippi, economic development in New York, and institutional services in Iowa). Given Klinenberg’s recent urban research of the community-wide impacts of social infrastructure, and what we heard from residents in rural towns, we focused our analysis on outcome differences between those with a permanent library place within its boundaries and those without.

EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES

That having a public library will improve an individual’s access to educational opportunity is intuitively understood by most people, even those who never use public library services. The question driving many studies of service and outcomes is whether or not having access translates into measurable increases in educational success. Research from Gilpin, Karger, and Nencka (2021) suggests that capital investment causes long term (greater than five year), lasting improvements to English Language proficiency for youth within five miles of a public library that has undergone massive renovation or construction (cost over $200,000). This study establishes a causal (not just corollary) relationship between service and impact by identifying a natural experiment, or “shock”, to study the community before and after the moment.

Rural Libraries & Social Wellbeing statistical analysis is not robust to the level of causality, but establishes a consistent, and statistically significant, correlative pattern of improved educational outcomes for students in rural districts with libraries when compared to those without them. Using the same dataset (Stanford Education Data Archive) as Gilpin, et al, we demonstrate a positive difference in standardized test performance (pooled across grades and inclusive of both math and language tests). Part of the Gilpin study was noting that the capital investment “shock” impacted the frequency of library programs and youth attendance at those programs. An elementary principal we interviewed in Wisconsin gives some insight into how, in practice, the public library and the school systems work in tandem toward better English proficiency outcomes:

“As elementary principal it’s been great too, because they’ve come into our school and have done story hour with our students. I’ve met with the librarian here, ‘Hey, should I do a reading program over the summer?’ But I don’t because they do such a good reading program here. … They come there and show families all the different activities that they do over the summer and hopefully get them excited. So, as a principal it’s been really good. It’s impacted me a lot because it’s been really a good way to get families excited about reading, get books in kids’ hands.” (Wisconsin, transcript #3-2-14)

SOCIAL CONNECTION & SELF-DETERMINATION

The importance of connection to others cannot be overstated as we struggle to recover from a global pandemic. One of the nation’s largest studies of resident perception of community life was conducted in 2010 through a partnership of Gallup and the Knight Foundation. Called the Soul of the Community study, it has influenced regional planners since its release because its findings were so insightful: the primary predictor of economic growth in a town was whether or not the people who lived there would recommend living there to people they worked with (Quach, Symanzick, Velasquez, 2019).

Rural Libraries & Social Wellbeing field research was conducted in resource poor, isolated communities with few or no other community anchors. Interviews with individuals opened with the prompt, “Describe your ideal community.” Every resident interviewed in Vermont and West Virginia, and all but one each in New Mexico, Idaho, and Wisconsin said they were living in their ideal town. Across the interviews, residents told the researchers that their choice to live in their remote community was a mix of tight social connections (I know everybody and everybody knows me) and a feeling of freedom that comes in living where one feels safe to roam and be oneself. Community members described social connection in terms of being seen as they are, feeling known by their neighbors, and the related confidence that they live in a strong network of mutual support and aid. It is this last element that allows older adults to stay in their community, even though access to necessary medical services could be as much as three hours away. They know if they need help, be it an emergency or car ride to a regular medical appointment, their neighbors will provide it without hesitation.

In these interviews with community residents, the library was repeatedly mentioned by subjects as part of their ideal community make-up: the friendly banter, the coffee, the local newspapers, the “old timey” service. In fact, “old timey” service was key to building feelings of connection and feeling known in newcomers, as well as long term residents who have never quite felt a part of the community where they live. This feeling and description of desirable library service was consistent across communities, including in locations where descriptions of “ideal community” were less perfectly aligned with the place where residents currently lived.

Lack of access to local decision-making processes correlates to lower satisfaction with a town. Lower rates of “ideal community” in research sites in Iowa (82%), Mississippi (64%), and New York (40%) correspond to lower senses of individual say over the current state and future of the community overall. In Iowa, where residents were prompted to describe why there was a gap between the ideal and current community, we heard that the ideal was some point in the past where the small town had an elementary school, a bank, doctor’s office, and a grocery store. In this remembered town of 40 years ago, they had perceived control over their daily lives—the education of their children, access to financial services, and medical information and care.

In one town in Mississippi, the consolidation of the local elementary school and a failed lawsuit by the NAACP to reverse the decision on racial equity grounds, was the start of a multi-decade feeling on the part of locals that their political decision-makers were not acting with their best interests at heart. And in New York, the rolling closure of major economic players left tourism in another town as the only industry and employer; the local population, once accustomed to higher wages in independent professions, were more likely now to be service industry clerks to monied vacationers, adding economic inequality to the social tensions between locals and outsiders.

Even in struggling communities, it is the opportunities and facilitation of connection with other people that residents point out as integral to their quality of life, and that sociology and public health research supports as determinate of both how good we see our life and how long we get to live it.

LIFE EXPECTANCY

How long we live has been tied to our income, educational attainment, and zip code in various studies over time. Recent research by Singh and Siahpush have demonstrated both consistency with other findings that living rural correlated with life expectancy two years shy of the average urban resident, but that the gap between these geographies has steadily widened over time (2014).

Public health policy research has noted that hospital and clinic closures, combined with the consolidation or disappearance of public and civic service institutions within rural towns would lead to declining health outcomes for residents (Sullivan, et al, 2020). Through statistical analysis using the Center for Disease Control’s national mortality data study, we show a gain of six months of life in census tracts with local public libraries compared to those without one.

SERVICES

There is no federal mandate that funds to states from the Institute of Museum and Library Services go to public libraries directly, and the extent to which these funds are used to support resource sharing and equity of service across geographies varies widely by state.

MATERIAL RESOURCE SHARING

Although library lovers everywhere love their library, where residents were aware of a resources sharing option the library was not involved in, we noted open disappointment over lack of digital or specialized (e.g., large print) offerings. In these field research locations, we heard residents say that they “have read every large print book in here” or “listened to every book on tape”.

Access to non-local works make a resident feel like the library was able to serve their individual passions and interests in a uniquely personal way.

Conversely, where cooperative resource sharing systems were in place and robust, including a regional delivery system and a way for local residents to search a regional or statewide catalog, library users noted it, too. They usually described how the library worker “looked up” a book, audiobook, or helped with a digital platform variously as “magic,” a “delight,” and “wonderful”. It helped increase the community residents’ feeling that the person working in the library was able to serve their individual passions and interests in a uniquely personal way. Where regional systems exist, requested material would arrive in a day or three, compared to non-regional interlibrary loan systems which tend to have turn around times of one to three weeks.

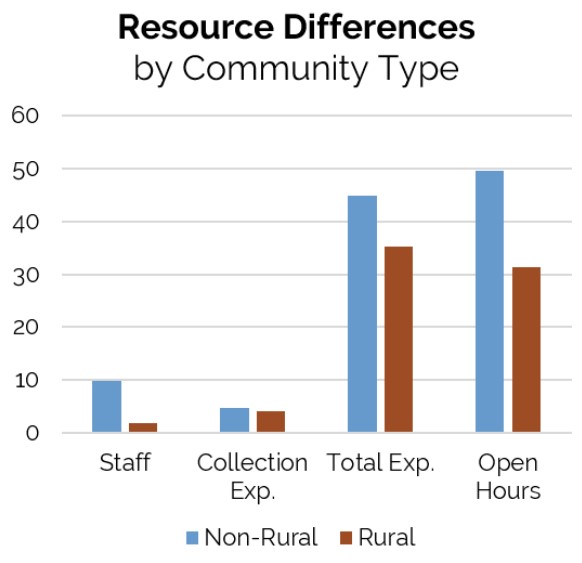

Resource sharing is one way to achieve service equity across regions with diverse population densities and funding bases. The average rural library building is staffed by the equivalent of 1.9 full-time workers2; this number includes all library programming, administration and grant-writing, maintenance, collection development and management, and event/volunteer coordination. Where there is no regional or state-wide resource sharing, rural libraries are typically on their own for collection management, which includes expensive digital licensing (at higher prices and worse terms than consortia can negotiate) and online catalog service. These are considered core services of 21st century libraries, with labor and contract costs that undermine other important local services.

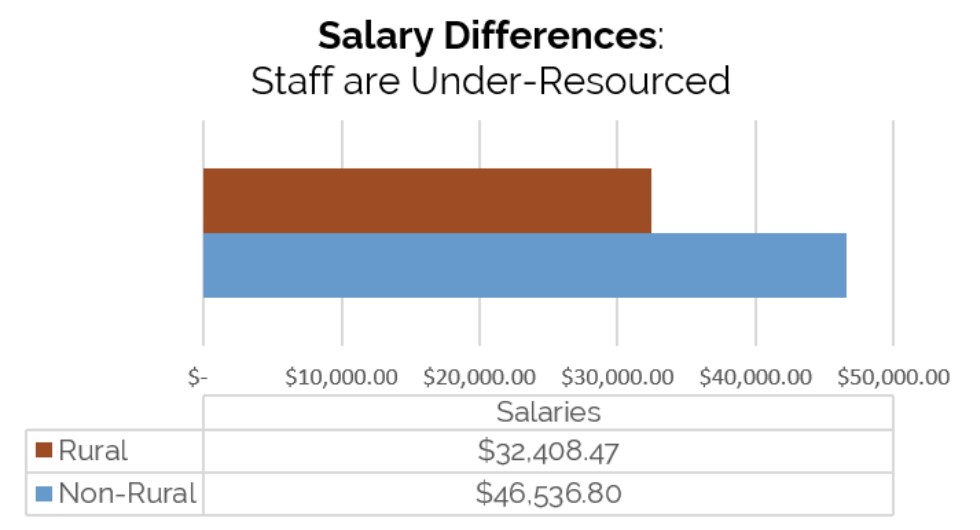

Additional resource access impacts on equity of service to rural communities. A review of fiscal year 2019 public library survey responses from libraries large enough to give salary information without compromising individual rights to privacy (double the average rural library staffing), salaries in rural communities are significantly lower than in non-rural places3. Further, they come with less specialization: with a staffing average of 2 people, one is likely to be the director or manager who wears all administrative, facilities management, and fundraising hats, with a programmer (usually specifically a children’s programmer) who does all the events and activities.

STAFFING & SALARIES

Resource sharing when done right, then, is also staff support. When regions can cooperate (with state based incentives and support) to centralize material resource support like cataloging, online catalog management, digital licensing negotiations, pick up and delivery of items, and reporting on these systems, an administrative burden is lifted off of the local library and it’s much smaller tax base.

Reports on rural public libraries commonly discuss the professional certification status of rural library directors and managers. In our research we noted that many people who held that position had backgrounds in education or healthcare, and graduate degrees were commonly held. What was far more rare is the Masters of Library and Information Science (MSLIS) degree.

Through interviews with over fifty rural library directors and managers we recorded themes on the MSLIS. Those without the MSLIS thought they would likely never be recognized in the field as professionals with ideas and practices worth considering, but that the expense of (another) degree did not make sense given the salary their town “could afford.” Conversely, those with the degree stated that their coursework was often misaligned with rural community library practice where skills in education, relationship building, grant writing, facilities management, and event planning are paramount.

OPEN HOURS

Rural Libraries & Social Wellbeing did not analyze library services like circulation or visit statistics. Instead this research attempted to tie the statistically significant positive community outcomes of living in a rural community with a public library and resident descriptions of service and place. In this way, the research design sought to uncover principles of practice that met community resident aspirations and values while building on the unique strengths of the public library as a unique anchor institution.

In finding and verifying the importance of social connection to positive social wellbeing outcomes and resident perceptions of quality of life, access to the facility that facilitates those formal and informal exchanges became a service of particular interest. On average US non-rural libraries are open 50 hours per week compared to 31 hours in rural communities. Limited open hours in communities with few or no other community anchors is an additional injury to residents.

POLICY CONSIDERATIONS & MORE ANALYSIS NEEDED

Robust outcomes require robust investment. As Klinenberg’s research in Palaces for the People posits, and our research affirms, public libraries are social infrastructure with far reaching, cross-sector impacts. This is all the clearer in examining rural communities where disentangling the effects of other community resources from those of the library is more straightforward, because there are simply far fewer resources.

FEDERAL BASE FUNDING

Few public institutions can be credited with improving how many people in a community learn to read, graduate high school, feel attached to where they live and get to live to their full potential age. Because public libraries are funded by the population they serve, the smaller the population, the fewer the resources to fund it. For this reason, we encourage an analysis of the cost and potential benefits of expanding federal grants to libraries to include a program similar to the funding program for US tribal libraries.

FEDERAL & STATE CAPITAL SUPPORT

The Americans with Disabilities Act was passed over fifty years ago and public libraries across the United States continue to fall behind other public agencies in serving individuals with mobility, vision, and hearing impairments (and relatedly, parents with strollers). Local governments and taxpayers who are the sole regular source of funding support for libraries rely on library directors to be continuous grant writers so that the community might enjoy programs or services otherwise financially out of reach to the town. Grantmakers are not commonly in the business of funding operations or capital projects. New York State currently provides one version of state led infrastructure support worth further research and analysis.

STATE LIBRARY DEVELOPMENT SUPPORT

Thirty percent of US rural school districts have no public library anywhere in the district. Finding locally relevant ways to start new libraries in underserved communities should be prioritized. There are few other partnerships state education and library agencies could engage that would deliver such large rewards in educational outcomes at such a small cost, than supporting the new development of permanent library facilities.

Rural Libraries & Social Wellbeing interviews demonstrated that what made the rural library impactful was the level of local community control and relevance of services and programs. State library development staff should consider funding, measurement, and reporting protocols that:

- Respect and save the time of library staff: they might have fewer than 2 hours a week for administrative tasks, which is when they are supposed to focus their efforts on grant writing and fundraising.

- Require only what is actually needed in order to keep the local library accountable to their public funders.

- Measure what matters and do not publicly reward libraries for statistical successes in areas directly related to the financial wealth held by their tax base.

CONCLUSION

People living in rural communities with public libraries are demonstrably better off than rural residents without a permanent local library. Rural libraries deliver robust and diverse services tailored to their local communities in buildings, on average, only slightly bigger than a single-family home. These small buildings are the central place and anchor in small towns, facilitating community member belonging, connection, and mutual support. And in so doing, they correlate dramatically to improved quality of life and multi-dimensional social wellbeing.

Rural school districts with public libraries boast higher student achievement scores and graduation rates. Rural census tracts with libraries bring rising rural mortality in line with the national average—a difference of six additional months of life. And where, in combination with having a public library, individual community residents are able to fully participate in decision making on a local level, those additional months will be spent in their “ideal community”—where they feel rich even without financial wealth, and safe even without nearby social services and medical facilities.

Community librarianship requires cross-discipline skills in education, relationship building, fund and facilities management, and community development that are rarely a focus of the LIS curriculum. One third of library outlets in the United States have a head administrator without a formal professional degree that may be out of their reach—or simply not worth the time and money for their salary— and little to no alternative pathways to achieve professional status. This unfortunately has the impact of marginalizing people doing critical social wellbeing work from having a voice in the field and minimizes the positive impact they could have on practice.

Policy makers, regional planners, and funders have a role to play in the success of rural communities by supporting the effectiveness of the public libraries which serve them. Resource sharing is one way to achieve service equity across regions with diverse population densities and funding bases. Incentivizing resource sharing practices at the federal and state level, as well as providing base funding for capital or operational expenses would reduce inequity between communities across regions.

Endnotes

- Rural Libraries & Social Wellbeing used the terms resource poor and rural throughout design, methods development, implementation, and analysis of the gathered data. This research uses the definitions established by the National Center for Education Statistics for designating the urban-ness of a school district, which is also used by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. Field research sites were selected from the nation’s “rural-remote” public libraries located more than 25 miles from an urbanized area and more than 10 miles from an urban cluster (p. 26, IMLS). When conducting statistical analysis, the project often pools results across small town and rural designations, maintaining distance from an urbanized area in combination with low population. Each analysis conducted by Rural Libraries & Social Wellbeing is published in Open Science Framework with the dataset and the specific steps followed to produce the findings.

- Though there is no national standard of the number of hours for calculating full-time equivalency to guide the local survey respondent.

- Analysis was done only on public libraries which are considered stand-alone entities where the public facing library is also the only library served by the administration working in that library and governed by its board. This required limiting the data on variable C_ADMIN to SO.