Pathways of Being Seen & Feeling Known toward Mutualism

Confidence that your neighbors are looking out for your best interests, will intercede if you are in trouble, and will notice your absence around town is a primary reason the people we spoke to felt comfortable living in communities which were far from common amenities like hospitals, schools, and grocery stores. Mutualism, or networks of mutual aid, are critical to aging residents and parents of young children alike. We heard that a key feature of knowing you are in a mutually supportive community was feeling known around town and being seen for who you are as you are.

One of the dimensions of social wellbeing we sought to measure in our research (like many other social indicators and determinants of health researchers) is social connection. How closely are people connected to one another and how deeply they trust those connections can have ripple effects throughout their lives: longer lives, reduced chances of dementia and depression, and increased sense of happiness.

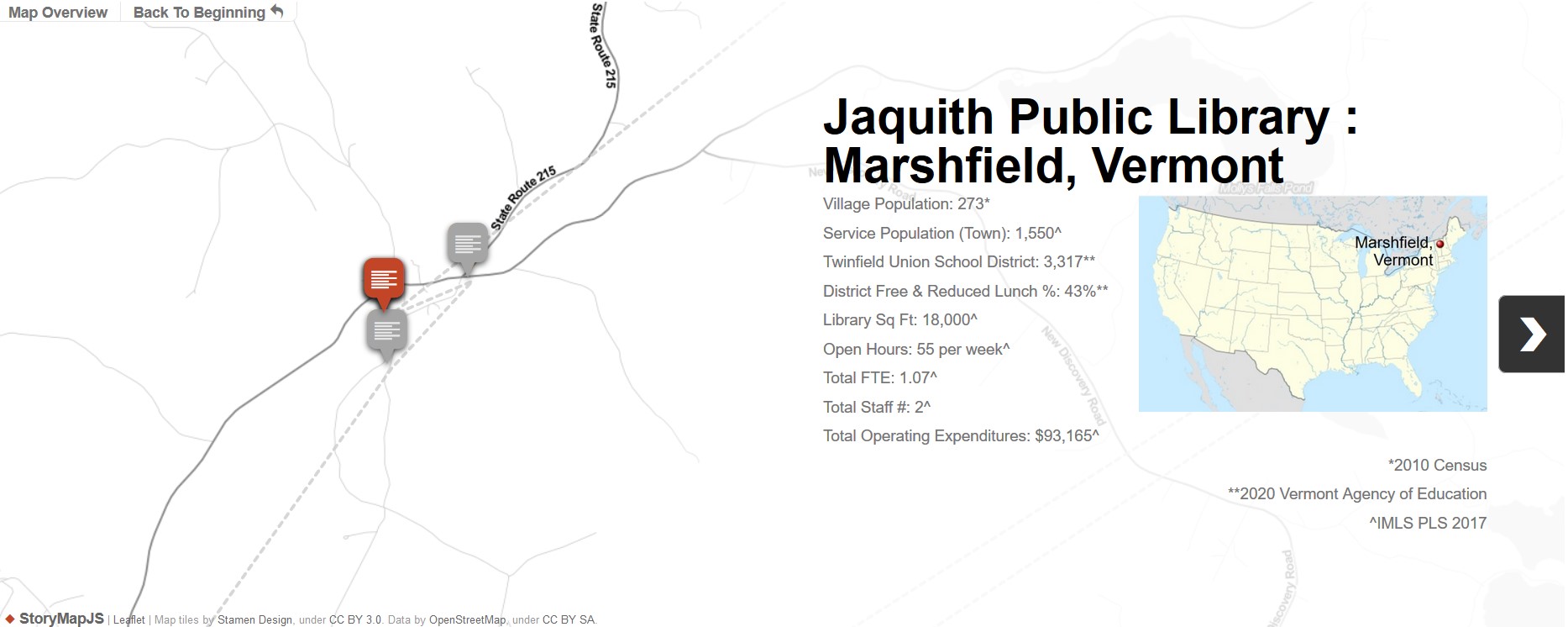

Mutualism and feeling seen & known was common across our study communities. What was uniquely evidenced in Marshfield was how the library director worked to support these feelings, the knock-on impacts of mutualism for self-determination, and the notion of residents that in knowing one another they can work on shared goals regardless of not-shared backgrounds.

How Being Seen & Mutualism is evidenced in Marshfield

Alive, vibrant, connected – all through the library and the converted school which the library is within.

“When I first moved here I was sort of bothered by how close a watch neighbors kept on me or just don’t know how nosy they were in other words. Now I just feel more comfortable. I know that there are people who will notice if anything is really different.” (Marshfield resident – transcript, #4-2-02)

Involved! Residents interviewed saw themselves and their neighbors as involved in community events, civic committees, and town government. Government officials described town meetings as moderately attended with members of the community speaking on topics of importance at every meeting.

Many people described a wish for a more racially and ethnically diverse community. Further, that there was more community member group cross-over at events. For instance, the group that attends Wednesday night supper is different than the group who attends the baseball group (moms and their elementary-aged kids) than the group that attends community-wide all ages kickball games. While each of these kinds of activities are well attended by a core group of people, that core group had little overlap with any of the others. The noted difference was the summer concert series in the park which runs for eight weeks. That was perceived as bringing every segment of the community together.

Marshfield VT is tucked between mountains and hills. An unhurried river runs through it creating the valley that joins it to neighboring towns. Other than the major routes between towns, most roads are dirt roads, which invites drivers to slow down. On one road I met a large brown cow who seems unfazed by my car as I carefully drove around her. I felt that I could just experience the landscape and the people I met. While I worked hard, it felt peaceful here.

There were ample trails to hike in Groton State Forest and the surrounding mountains. People were grateful for the natural resources here. Protecting the environment was a priority that people felt deeply committed to. I heard people talk about having a zero carbon footprint and the practical ways they were implementing it personally (riding a bike instead of owning a car, even in winter with small children) and advocating on a broader scale (getting more bus routes). Small farms were plentiful, the terrain didn’t lend itself to large scale farming. It felt like everyone was a little closer to the land. In fact, several people spoke about how the back to the land movement had shaped this area. It created a sense of dedication to place that I had not felt elsewhere.

The library is located in an old school, which also holds the town offices, the food cupboard, a gymnasium, a kitchen and several small businesses. There is a playground and a gazebo outside. Many people told me about how the library-sponsored concerts in the gazebo made them feel more unified. This is a community that is intentional about fostering connection. People care about one another. The weekly community suppers were a beautiful, crowded and slightly chaotic affair. People were contributing in the kitchen, bringing a dish to pass, catching up and sharing a meal. I had the most delicious tomato I’ve ever tasted. It was an heirloom Brandywine, perfectly ripe, just picked and still warm from the sun. In that moment I wondered if life could get any better.

Sense of place tied to independence and the Vermonter’s way of life. This appreciation of each individual’s right to independence is part of the back to the land movements of the 1950’s – 1970’s that augmented the generational agricultural community in this part of Vermont. These mash-up communities have matured into a culture of place that believes in public goods, mutual aid, and privacy.

The close-knitness of Marshfield allowed parents of young children in interviews to express that they would not hesitate to leave their children with any one of their neighbors in case of emergency.

Clear-eyed recognition that moving all services plus businesses into the school was a great boon to community social infrastructure.

Library as Facilitator of Mutualism

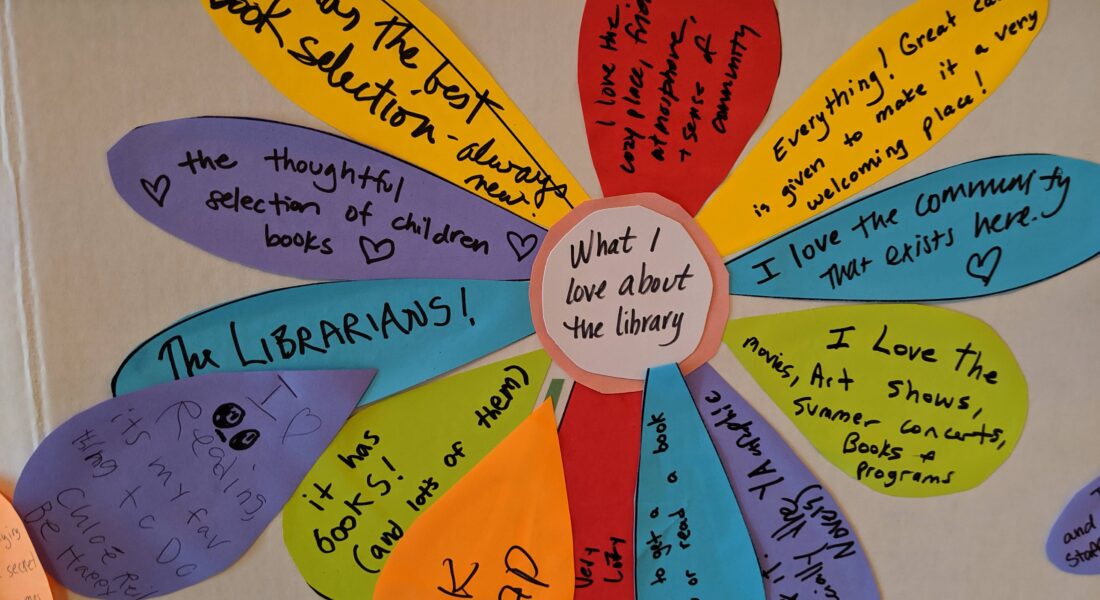

In addition to abundant natural resources, residents described the ways in which the built environment and community lay out improved their sense of place and supported civic voice and engagement. Alive in many interviews is the idea that any ideal community would have a vibrant public library. Individual voice and ownership in the library is reinforced from birth as every child born into the Marshfield community has a book named for them in the library. As they grow older they can search the shelves for their book and the books of their friends.

Although there aren’t many traditional industry jobs in Marshfield, the region supports a robust sharing economy that runs through its sense of social connection and community wellbeing. Often using the library as organizational hub, this informal economy includes weekly free community suppers, used book sales, and community-wide clothing swaps. Residents shared that the renovated school infrastructure allows for these sorts of continuous large group events. Even though the infrastructure stretches beyond the library, the library itself is seen as the catalyst for public goods and sharing.

Isolation from medical services and grocery stores is mitigated or supplanted by a community culture of food sharing, growing, and trading. Informal community agriculture is supplemented by large scale dairy, meat, and produce farms which sell at the market in Marshfield.

Tight social bonds, feelings of relaxed and comfortable safety for oneself and one’s children runs through all the interviews. There is a sense that although formal agency social safety nets aren’t robust in town, the informal community based safety nets are strong enough to make-up for the lack.

Isolation from entertainment and healthy pursuits is especially difficult in the long winters. The library continues to hold regular programming throughout the foul weather, including supporting the weekly community supper and programming which follows.

For those few businesses, agencies, and start-ups that rent space in the school, the library’s investment in T1 broadband connectivity means the ability to operate. Director Susan Green shares that the first business to make use was a medical transcriptionist who said that broadband connectivity was building feature that allowed the business to exist and thrive. Community members in turn, appreciate all that the library does for the community. No one could remember a single library budget cut in the history of the library in the renovated school building. Although cuts had been proposed by the town board, the community reacted with vitriol against any move against library funding.

Even in this tightly woven community, some residents described that getting to know their neighbors couldn’t have happened without the facilitation and support that library gatherings provide. It is a comfortable middle ground for people to discover their common interests and goals. To meet and to get involved in common efforts.

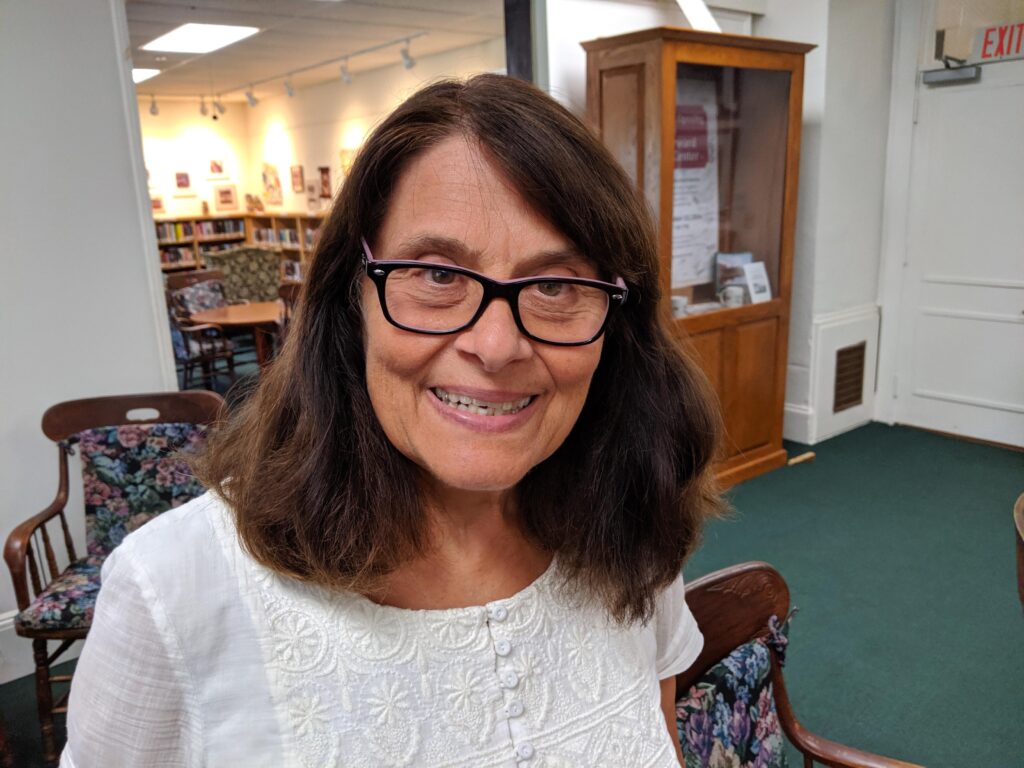

Director Susan Green’s actions as organizing conduit includes helping community members unleashing self-identities they had always kept private. One local painter and exhibiting artist relayed that she began to see herself as an artist in her mid-70’s when Susan saw her paintings and asked her to show them at the library. In the six intervening years she has lived up to her artist identity, showing and selling her paintings throughout her region of Vermont. She thought, “Who are you kiddin, you’re 80.” when deciding whether to submit her work to juried shows. But, “it’s validated a very important part” of her life which she felt had been “neglected” until Susan’s invitation.

The library now holds an annual show of local talent, including poets, playwrights, performance and visual artists. This expressive function of the library contributes to and feeds Marshfields sense of shared identity as much as the History Center Susan helped establish in the library. They value self-expression as well as collective action.

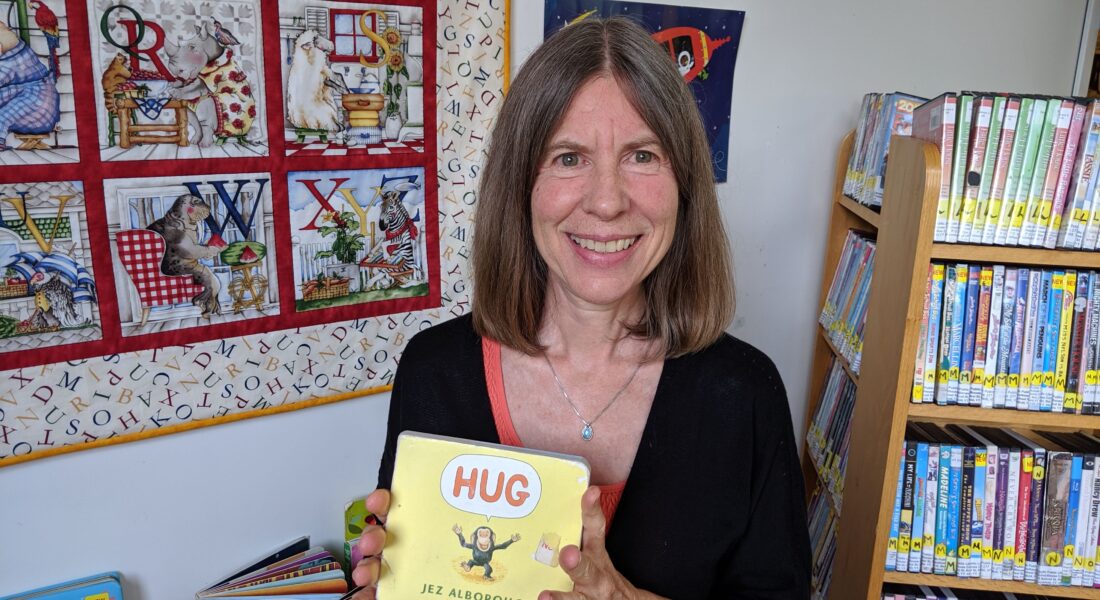

As a group, residents interviewed in Marshfield detail an experience in the library that is comfortable and pro-community. Part of that comfort for families comes from the building itself – approachable on the same campus as a playground. But the other part is intentional policy and treatment by staff and volunteers. There is no shushing in Jaquith Public Library. Although all residents treat the space with respect, no books, toys, or furniture are treated as precious to the extent that it limits their use by toddlers.

Other building elements include the local history room. It is to find a library as evenly committed to vibrant all-ages programming and the preservation of local history. For Marshfield residents local history, including artifacts of heirloom technologies and farm implements, comes part and parcel with their current civic and cultural engagement. The naming of the Hap Haywood Local History room refers to a volunteer and local artifact preservationist whose collection became the foundation for the room’s rich displays.

The library is a trusted place to access information and education. This trust allows it to host programming which some people could find challenging or uncomfortable, including sessions from Black Lives Matter. In Marshfield, like in many locations researchers visited, there is a current of residents who wish for a more racially and ethnically diverse community. Marshfield is the only place visited where as a community they directly engaged in questions about why their community might be unwelcoming to anyone other than white people. Multiple community members discussed issues of racism as a whiteness problem in their town, and that their community was missing out by being overwhelmingly white.

Director as Pathbuilder

The story of Susan Green at Jaquith is a story of intentionally constructed sustainable practice.

Like many hometown libraries, Susan is seen as smart, friendly, open, creative, and hardworking. Unique to her practice is the impact of how she sees herself. Susan Green is a conduit and organizer of the brilliance in Marshfield, Vermont.

Networking is not an uncommon skill among professionals. Susan’s community-first approach is to use her networking skills to connect community members together. Although many residents described the library as a community hub, drawing out the network of connections that the library facilitates is significantly more distributed. Most community nodes connect to the library, but they also have dozens of connections to other individuals and organizations throughout the Marshfield / Plainfield region.

Welcoming new-comers and long-term residents alike into a “caring community” is Susan Green’s primary responsibility, as she sees it. One recent arrival to Marshfield said it was the library’s response to her phone call asking about story-times that made the decision for her family to buy in Marshfield. As employees in Montpelier, they were looking for the right small town to settle in, so they called all the libraries in the region to find out about services for their kids. The warmth and enthusiasm of Jaquith Memorial Library staff made the choice easy.

The economic knock-on benefits of creating this positive sense of place is intentional. Susan says that part of her reasoning in constructing this culture is so that people invest in the region’s abandoned housing stock and rebuild the population of Marshfield and Plainfield.

Supporting and trusting staff, like Sylvia, and volunteers. They may have approaches and needs that are different than Susan herself may have, but theirs are valuable and resonant with segments of the community, and are made part of the library approach.

Susan quitting her job would not end the library service program.

Conclusion

“We want to be part of a group that we can feel like we are heard and we can make some difference. And I think that, you know, Marshfield exemplifies that. We have a elected select board, you know, people can run and they – we know them. They’re not there’s not any great bureaucracy.” (Marshfield resident – transcript #4-1-01)

Intentionally building tight social connections, by recognizing individuals and their unique talents created a deep sense of shared responsibility and collective action which defined Marshfield’s identity.

Related Resources

Pathways of Mutualism toward Health & Security: Case Study in Elk River, Idaho

Being Seen & Feeling Known tool: Pathways of Belonging: To Be Seen & Feel Known Assessment

Being Seen & Feeling Known tool: Is Everyone Welcome at Your Library?

Mutualism tool: Community Support Assessment

Mutualism tool: Identifying & Preventing Burnout

Listen to or read the interviews: Site 4 on Open Science Framework