Pathways of Lifelong Learning toward Self-determination

Self-determination is inextricably linked to power. And although we often think of power in terms of its political or economic expression, pathways of self-determination can be built on the nature of, and control over, one’s learning. Feelings of self-determination, or control over one’s own future, relate directly to their own social wellbeing. When action is perceived as having a useful personal outcome within the control of the actor, they are more resilient in the face of challenge and express higher levels of satisfaction, safety, and health in their lives. Across communities of study, we often saw self-determination expressed in terms of economic power. It was only in Helvetia, Elk River, and Abiquiú that we heard it tied explicitly with knowledge creation, learning, and expression. Pueblo de Abiquiú’s example is the most multi-layered and robust.

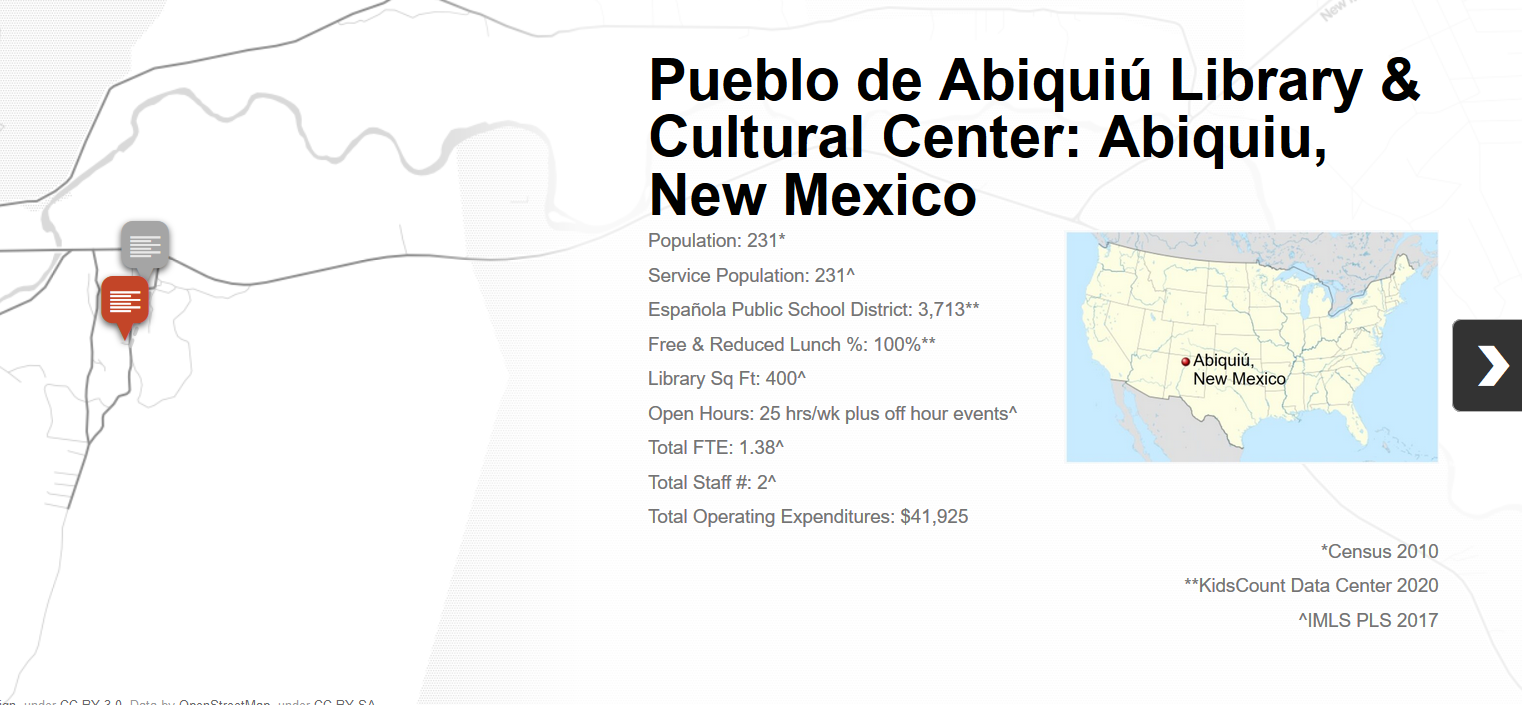

How Lifelong Learning & Self-determination are evidenced in Abiquiú

Abiquiú is a small but complex town of many stories. If you were just passing through, you would likely be struck by the simple beauty of the surrounding hills, seemingly ancient houses, and incredibly picturesque adobe church. But it is far more likely that you came to see the house and gardens of Georgia O’Keeffe, or because you read one of the many books and articles written about the rich history of Abiquiú, including growing scholarship about genizaro people. Virgil Trujillo, a generational landholding resident in Abiquiú described the community as built on four cornerstones: culture, faith, family, and land.

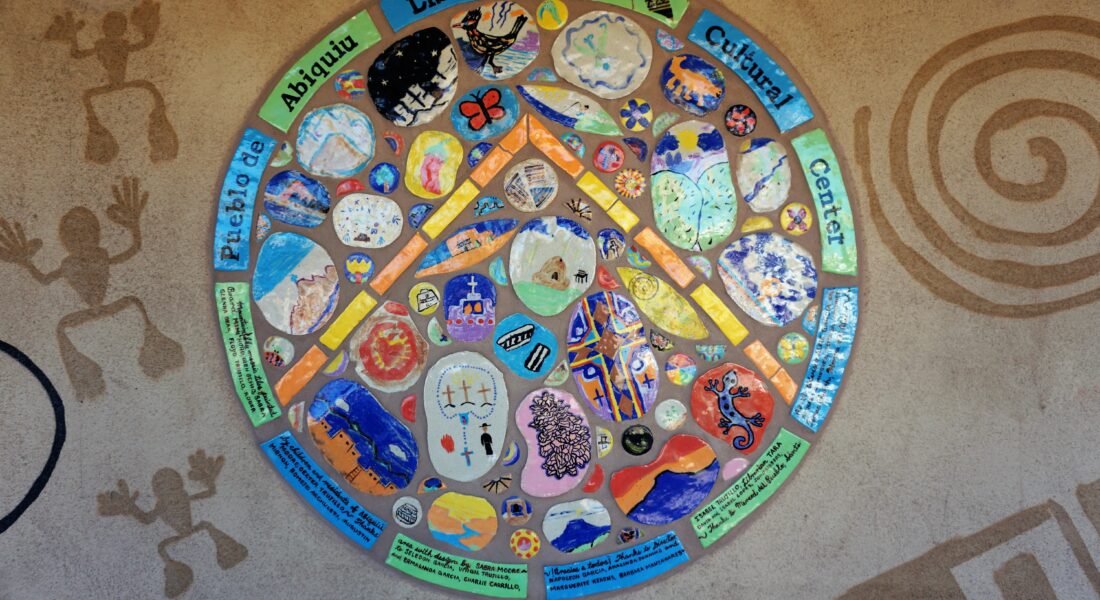

Along the highway are lavender gardens, quaint inns, and a hip restaurant/general store, but when you exit to take the short road that leads to the town itself, commerce becomes non-existent, as does signage of any sort. Tourists wander around the central plaza in confusion. Where are the restaurants? The gift shops? Which house is the famous O’Keeffe house? Eventually visitors discover an open door that will lead them to the answers, underneath Tibetan prayer flags, surrounded by murals: the El Pueblo de Abiquiú Library & Cultural Center.

The Library & Cultural Center is compact, to say the least, but makes good use of its space. In the main room, where the circulation desk sits, two large and very solid wooden tables are surrounded by stacks with displays that feature local interest books and articles. Here, locals can read the newspaper and tourists can check email on their laptops. It is not uncommon to find a child reading a book in the little children’s area, or a local resident to be in the small computer lab. A lovely back courtyard shaded by a large tree provides additional space for staff or patrons to stretch out.

Abiquiú has two distinct populations, at least: the locals whose families have lived in the same spot for centuries; and the artists “newcomers” (many have been in Abiquiú for decades), who came chasing the hills of O’Keeffe and never left. By and large where the newcomers have shown respect and deference to the place and the local people they have made strong connections and are welcomed. But this place is also littered with stories of newcomers who came, stayed briefly, showed disrespect, and went.

To this mix has been added in recent years the miniature tourist industry that surrounds Georgia O’Keeffe, and the staff of the O’Keeffe Museum, her Abiquiú residence, and the nearby Ghost Ranch. When you search for the home where this artist lived in for so much of her life—and where so many other artists visited her and created their own art—you find yourself inside her paintings, surrounded by the very scenery that she represented and that represents her. It is a beautiful and complex Northern New Mexico town, where history lives vividly and the stories told very much depend on who is telling them.

Abiquiú Culture & Power

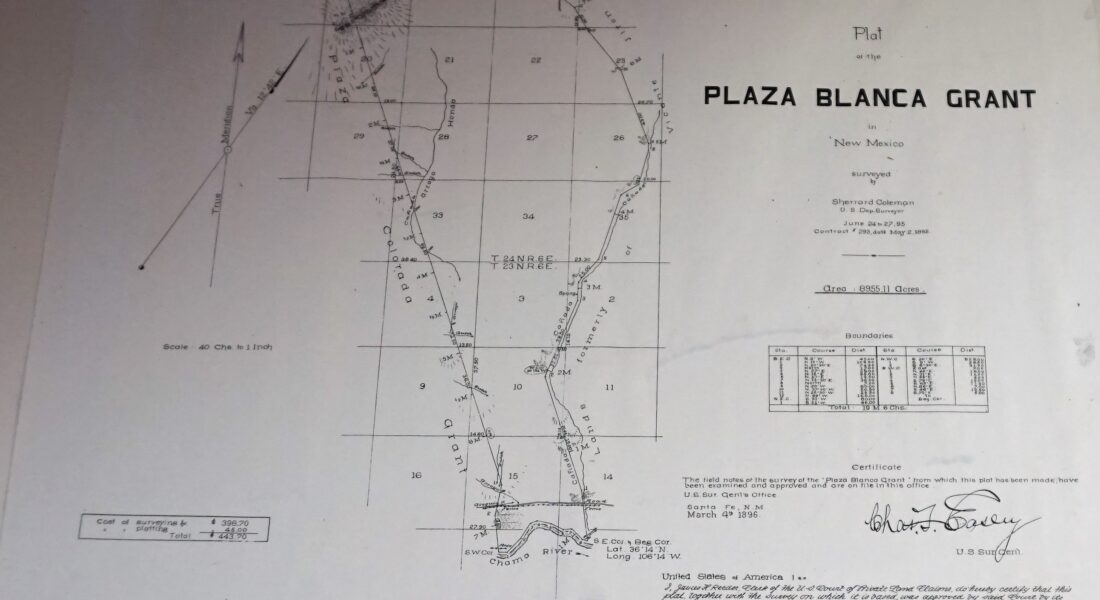

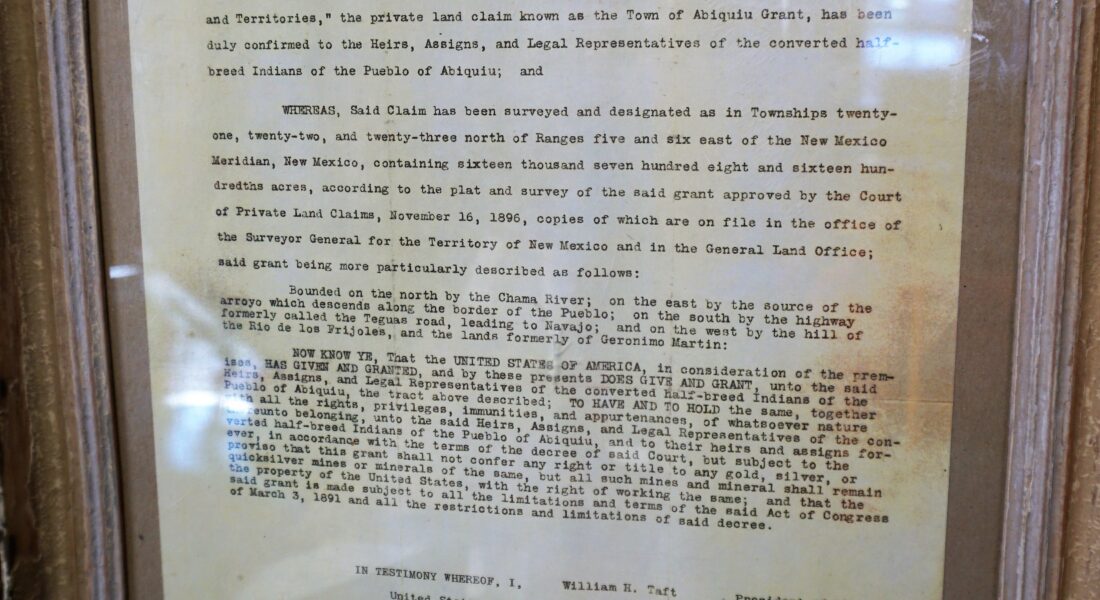

Cultural engagement is defined differently in Abiquiú depending on where in town one lives, what their occupation is, and with which organizations they most closely align. For instance, some residents of Abiquiú own ranch, farm, and residential lands as part of a Land Grant specific to their Genizaro heritage. This group of families was given land as a reward for their military service and to provide a buffer between Apache, Comanche, and Navajo peoples and the seat of colonial government in Santa Fe. The Land Grant agreement was kept when New Mexico became a state by then President Taft–this declaration is on framed display in the Pueblo de Abiquiú Library and Cultural Center. These families still operate a Land Grant Board which makes decisions about all commonly held land, giving them a great deal of local decision making power regardless of their actual residency status.

Nearly every person interviewed talked about St. Tomas Church, even if they themselves would not call themselves Catholic. Those practicing faithful shared that they no longer have a local long term priest in residence–rather, the Father is shared between many rural parishes in the Carson and Santa Fe Forests north west of Santa Fe, and is replaced around every three years. This practice is new to these communities in the last couple of decades and is seen as part of the degradation of spiritual and social support to the community.

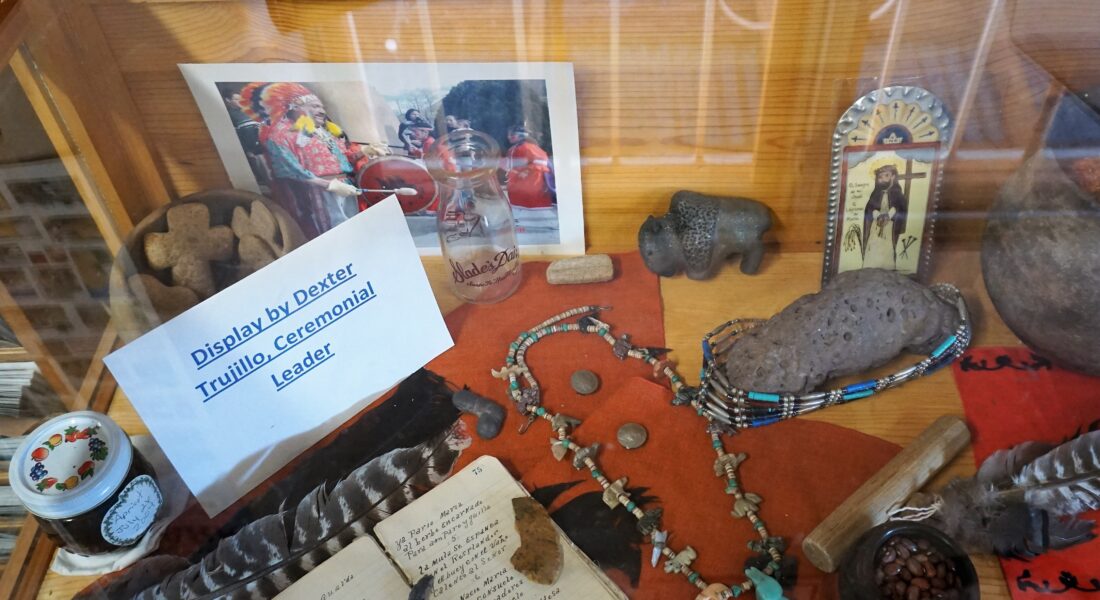

Catholic holy days, the celebration of the saints, and decision-making power of the diocese were very much a part of the cultural fabric in the community, regardless of faith. As board member and Ceremonial Leader for the Pueblo, leader Dexter Trujillo shared that Fiesta de Santa Rosa de Lima is an expression of European identity in Abiquiú, and that “Apostle Santo Tomas is the Indian part of us” (transcript, #7-3-02).

As if to highlight the cultural and decision-making nature of faith organizations in Abiquiú, the library is in a building owned by the Catholic Diocese, and their bookkeeper is a founder of Dar al Islam, an Islamic education center built in Abiquiú in 1979. And to display the simultaneous deep rootedness of Pueblo de Abiquiú and its cosmopolitan appeal, the Georgia O’Keefe house occupies a large portion of the mesa it shares with the library and many of the board members did not grow up in Abiquiú.

This history of colonization and erasure is not uncommon in New Mexico. As it presents in El Pueblo de Abiquiú, embattlement has led to deep divisions about shared narratives. Who owns the story of a community’s residents? Their own lived experience? Their varied relationships to Georgia O’Keefe and her transformational presence? Which language is spoken and who chooses? What are the consequences of limiting the diversity of community narratives?

Library as Facilitator of Learning & Self-determination

The library is 400 square feet of condensed power–board and staff have the notion that if they were just a library, they would have been required to stay within those walls. And that in renaming themselves they were liberated to serve the culture, history, and social lives of their community members.

Although literacy is widely regarded as a tool of self-determination, in Abiquiú multiple literacies are understood as pathways to power. At a book club meeting here I heard the story of how, in her later 20’s, a participant learned to read through her friendship with another book club member and the support of the group. It was her story that illuminated most clearly how pathways work: an entry point which is usually a person eager to invite you along; a path that might be horribly challenging, but with a trail guide and markers along the way is able to be traversed; vistas, like meetings with your book club friends, that show you what the wide-expanse of possibilities are if you are able to continue along the path; and celebrations which mark the end of a journey with enough love that one is motivated to take up another.

The El Pueblo de Abiquiú Library & Cultural Center, like many public libraries across the nation, is the entry point for visitors and new residents to town. What they learn is that the institution is invested in building literacies of residents, especially youth, that reinforce the community’s four cornerstones: culture, faith, family, and land. Here, one can attend monthly Herbal Literacy classes – a mix of botany, curandera history, and culinary delight. Or the annual Read-and-Draw where residents take turns reading aloud a single book based in or around Abiquiú in its entirety while attendees draw what they are thinking as they listen to the stories. In the end, library trustee and artist Sabra Moore sews the drawings into a single book — another tidy metaphor for life in Abiquiú and the coalescing power of the cultural center and library.

Across communities of study, the research shows how public libraries work as an organizational hub for residents and local organizations. In Abiquiú, it also operates to contextualize (and often to complicate) culture, faith, family, and land. Multiple residents indicated in interviews that the complex history of Abiquiú and the story of the people there had been iteratively erased over centuries. Where many communities when embattled against cultural erasure will pull in on themselves, make secret their knowledge and rituals, and create protections for their stories (Pertusati, 1997**), the library and cultural center has been key to doing the very opposite in Abiquiú.

The facility is home to preparations for feast days of Santa Rosa and Santo Tomás. While this may sound like it holds only a relationship to Catholic faith, as in all things Abiquiú, the reality is complex. Because this land was granted by the Spanish Crown (and later by US President Taft at statehood) to Genizaro families, heritage of the place, like Genizaros themselves, is a mix of Puebloan, Hispanic, and Comanche genetic and cultural histories. And so, celebrations hold this nuance within them.

And while both feast days have been continuously celebrated for hundreds of years in Abiquiú, it is through the work of the library that they have renewed context. As Sharon Garcia, lifelong resident and current Librarian states, “We were dressed up and danced like Indians”. She thought of it as costuming, play-acting, not a part of her own identity, until the library embarked on a partnership with Genizaro scholars to do a genetic study of residents in the pueblo.

Youth of Abiquiú are tied experientially to this rich past not only through genes and library programming, but through active participation in building the cultural record. With the Berkeley- Abiquiú Archaeology Collaborative, local teens work (for pay) every summer with graduate students and professors from the University of California Berkeley Archaeological Research Facility on sites around the ancient pueblo grounds and the Library and Cultural Center building itself. In addition to the physical labor provided on the dig, they learn and do GIS mapping, aerial, digital, and archival photography, drone maintenance and control, and recording and archiving of artifacts. The building is filled with the work of local youth: their photo stories rim the walls along the ceiling line, artifacts fill display cases, and they speak at local events on the history of place.

This work does more than give context to history past and present that seems, through commercial interests, to be continuously crowded by the O’Keefe legacy. It grants youth self-determining power grounded in their own legacy. They see themselves as scholars. This identity holds into adulthood with Abiquiú youth growing into adults pursuing PhDs in history, ethnography, and regional planning programs. They enter the adult world not having worked only at the gas station or the gift shop of the O’Keefe museum, but owning digital, cultural, herbal, visual, and textual literacies.

Director as Path Builder

Isabel Trujillo describes heaven on earth as a place where each of us would give joyfully and without expectation of return.

The bonds of mutual aid are their own reward and all community members enter into those relationships with a glad heart. This vision shapes all of Isabel Trujillo’s work at the library–work which prioritizes strengthening social connection between residents and grounding residents to the history and culture of place.

“If it wouldn’t be for Isabel that pulls us really by the neck, we wouldn’t even have a library because she’s the one who shouts and pouts and is a go getter and she doesn’t give in.” (transcript #7-3-02)

Isabel has led the Library & Cultural Center for over a decade, beginning as a volunteer and building her position along with the institution. As in most rural libraries, the success of services and programming is in part about the collaborative relationship of two leading staff persons. One person is often the children’s programmer and another the adult focused person. Isabel’s role as director mainly takes place outside the library and in library closed hours.

This naming distinction is unique to Abiquiú , and obscures how overlapping the roles can be. For instance, if there is a library program, for any age group, happening in the library, Isabel is involved. The volunteer who works with librarian Sharon Garcia to host the summer reading program at the library said that Isabel serves an assistant role to them as programming takes place.

And during large feast day celebrations and other community-wide gatherings in the plaza or the public gymnasium, Sharon is the face in the open library. Regardless of celebration day or time, the library opens for community events. Isabel operates as host, community member, and facilitator within the event. And Sharon acts as welcomer, director, helper, and friend to all who come into the library.

Sharon’s role providing what some would consider more traditional library service means that for newcomers to the community, she is the library. She is the person there to orient them to community history, to in-house services like wireless internet access, public access computers, fax/scan/copy/print services, as well as vast local history and culture resources. Any visitor to the building immediately sees evidence of both the history of the place and the current local construction of culture. Every wall, every shelf, every display case tells a specific story of Abiquiú – from the “Bless Me, Ultima” movie poster (shot outside the library), to the framed Land Grant document, to the local student made photographs of community – that need a guide for the newcomer to fully understand each artifact’s meaning. Sharon helps the visitor navigate all that condensed richness.

Conclusion

The Library and Cultural Center in El Pueblo de Abiquiú , which itself is in the town Abiquiú is a place invented by waves of people trying to capture and tell a complex story in a way which will resonate with visitors and inspire young residents to stay. While the services this library provides are not radically different from those provided in public libraries across the US, how they are done, how they are framed, how they are specifically constructed to relate a cultural heritage and natural context rooted to this exact place is unique. The place itself has a history that is rich and nuanced. Knowing it requires a living forgiveness and grace not often demanded of the amateur local history buff. It is a beautiful place that everyone should visit once and listen intently to the extraordinary diversity of stories experienced there.

Related Resources

Pathways of Contribution Toward Belonging: Case study from West Virginia

Self-determination through community knowledge tool: Preservation & Community Story

Self-determination tool: Building Local Political Voice & Power

Self-determination through community knowledge tool: Fostering Knowledge and Discovery

Newcomers tool: Library as Welcome Center

Listen and read interviews: Abiquiu audio and transcript files on OSF

Director bio & contact: https://rurallibraries.org/team/isabel-war-trujillo/

Panel discussion with Pueblo de Abiquiu Library and Cultural Center Director Isabel Trujillo:

**Pertusati, L. (1997). In Defense of Mohawk Land: Ethnopolitical Conflict in Native North America.